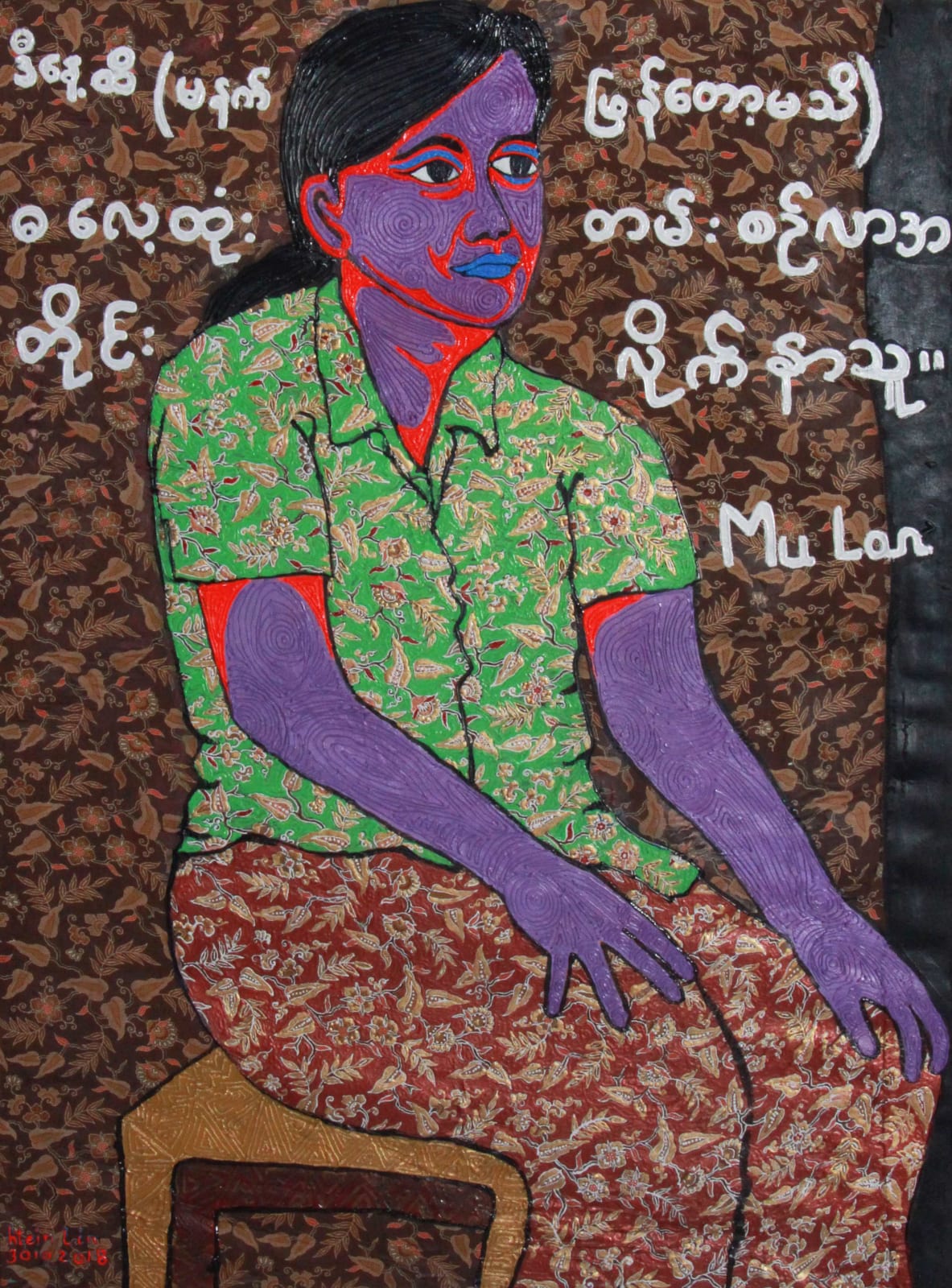

Htein Lin

Mu Lan, 2018

Acrylic on textile

Original Sizes Available:

91.5 x 122 cm

91.5 x 122 cm

Htein Lin’s latest project explores the concept of ‘hpone’, which means power, glory, or influence. Hpone is accumulated through meritorious deeds in a past life and only achieved by men....

Htein Lin’s latest project explores the concept of ‘hpone’, which means power, glory, or influence. Hpone is accumulated through meritorious deeds in a past life and only achieved by men. Hpone-gyi – meaning ‘big hpone’ - is Burmese for monk.

It is widely believed in Myanmar, by both men and women, that a man’s hpone, or masculine power, can be weakened by contact with women’s clothing and in particular clothing from the waist down, including the skirt-like longyi (or htamein to give it it’s precise name as a woman’s longyi). It is not unusual for a mother-in-law or sister-in-law to accuse a wife of failing to look after her husband and undermining his strength just because she is washing their clothes together.

These beliefs have been used to political effect. For example, opposition activists used to organize panty protests against the military regime, creating stickers depicting the generals, which could be stuck into knicker drawers. An National League for Democracy (NLD) activist Chaw Sandi Htun was arrested just before the election in 2015 for commenting on the similarity between the colour of the army uniforms and a green longyi worn by Aung San Suu Kyi, and suggesting that supporters could wear a piece of her longyi as a bandana. (https://www.mmtimes.com/opinion/17047-military-skirts-issue-of-powerful-women.html).

“I have painted on longyis before, when I was in prison, and the white cotton longyi of the prison uniform was the best available canvas. I would persuade departing prisoners to give me their old uniforms, but I only obtained them from the men.”

Htein Lin says, “With this project, I am inviting women to bring me a used longyi, in return for which I give them a new one. I paint a portrait of them on it, and discuss the question of hpone with them. I then invite them to write some thoughts about what this belief means to them, and how it impacts on their daily lives. Some have commented on its impact on where they hang their longyis out to dry. Another told me how she washes her husband’s longyis together with her own when he’s not around, but make a show of doing it separately when he’s there, to reassure him.”

Skirting the Issue began with workers and female friends and family based in the industrial zone in northern Yangon, where my studio is located. But as the word has got out about the project, I have had requests from my female artist friends to participate. With many of them strong feminists, their views may not represent the majority of Myanmar women today, but they may be the voice of tomorrow.

Text on Painting says, Mu Lan: Today I still follow traditional beliefs. (Tomorrow, I can’t say).

It is widely believed in Myanmar, by both men and women, that a man’s hpone, or masculine power, can be weakened by contact with women’s clothing and in particular clothing from the waist down, including the skirt-like longyi (or htamein to give it it’s precise name as a woman’s longyi). It is not unusual for a mother-in-law or sister-in-law to accuse a wife of failing to look after her husband and undermining his strength just because she is washing their clothes together.

These beliefs have been used to political effect. For example, opposition activists used to organize panty protests against the military regime, creating stickers depicting the generals, which could be stuck into knicker drawers. An National League for Democracy (NLD) activist Chaw Sandi Htun was arrested just before the election in 2015 for commenting on the similarity between the colour of the army uniforms and a green longyi worn by Aung San Suu Kyi, and suggesting that supporters could wear a piece of her longyi as a bandana. (https://www.mmtimes.com/opinion/17047-military-skirts-issue-of-powerful-women.html).

“I have painted on longyis before, when I was in prison, and the white cotton longyi of the prison uniform was the best available canvas. I would persuade departing prisoners to give me their old uniforms, but I only obtained them from the men.”

Htein Lin says, “With this project, I am inviting women to bring me a used longyi, in return for which I give them a new one. I paint a portrait of them on it, and discuss the question of hpone with them. I then invite them to write some thoughts about what this belief means to them, and how it impacts on their daily lives. Some have commented on its impact on where they hang their longyis out to dry. Another told me how she washes her husband’s longyis together with her own when he’s not around, but make a show of doing it separately when he’s there, to reassure him.”

Skirting the Issue began with workers and female friends and family based in the industrial zone in northern Yangon, where my studio is located. But as the word has got out about the project, I have had requests from my female artist friends to participate. With many of them strong feminists, their views may not represent the majority of Myanmar women today, but they may be the voice of tomorrow.

Text on Painting says, Mu Lan: Today I still follow traditional beliefs. (Tomorrow, I can’t say).